This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Welcome back. One threat to European security is a Russian military victory over Ukraine. Another is that Donald Trump will win November’s US presidential election and withdraw or discredit the American defence guarantee of Europe. Should, then, European countries have their own collective nuclear deterrent? You can find me at tony.barber@ft.com.

My question has three aspects: the disintegration of the post-cold war global nuclear arms control regime; Russian nuclear sabre-rattling since its 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine; and the difficulties facing Europe as it searches for a credible response.

Nuclear arms control: is anything left?

An authoritative survey of the disorder that characterises nuclear arms control appeared last month in this report by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It opened with some blunt language:

The current global arms control regime is in disarray. Treaties that were once the pillars of the arms control regime have collapsed.

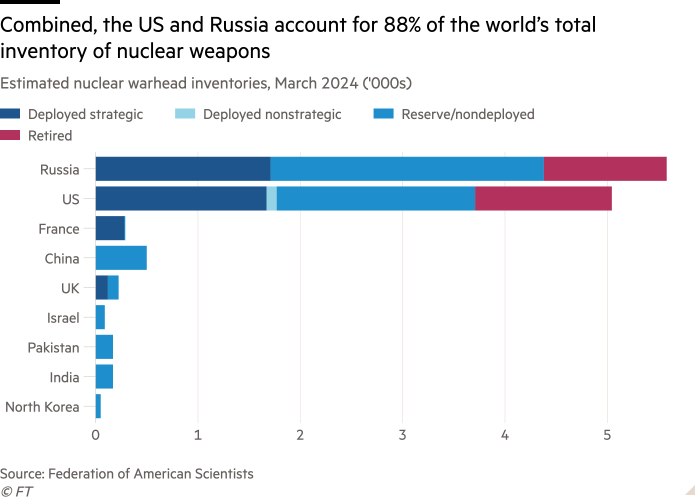

These treaties were primarily between the US and the Soviet Union, and then the US and Russia. Taken together, they reduced the global nuclear stockpile from 70,400 warheads in 1986 to about 12,500 today.

In its own survey, the Economist magazine wrote in August:

That era is ending, for four main reasons: America’s abandonment of agreements, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s nuclear build-up and disruptive technology.

Technology and verification

Technological advances are of particular concern. In the AAAS report, George Perkovich explains that the US, Russia and China are developing techniques to threaten targets with malware as well as kinetic and nuclear payloads.

At the same time, innovations linked to nuclear weaponry such as artificial intelligence and cyber capabilities are extremely difficult to quantify and verify. It follows that any future nuclear arms control accords will need to be considerably more sophisticated — and perhaps harder to reach — than the pacts of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Another problem is the expansion of China’s nuclear capabilities, carefully laid out in this article by Patrick Zoll for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. China was never party to the Washington-Moscow accords of the post-cold war era. It would be a mighty challenge to arrange three-way negotiations in the present climate of mistrust between the US on one hand and Russia and China on the other.

Proliferation

A third issue is nuclear proliferation. At present, nine countries are known nuclear weapon powers: the US, Russia, China, France, the UK, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. Iran is close to joining the group.

But what if the US nuclear umbrella no longer extended over its European and Asian allies?

In a separate article for the NZZ, Ulrich Speck contends:

The first movers in such a scenario would be countries that felt highly threatened, and which also had the requisite technical and economic capabilities.

He lists these as, in Asia, Japan and South Korea; in Europe, Poland and Ukraine; and in the wider Middle East, especially if Iran became a full-blown nuclear power, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

Moreover, German inhibitions about going nuclear might diminish if Berlin failed to establish a new protective umbrella for itself with a friendly nuclear power, specifically France, Speck says.

Russian rhetoric

For European governments, a grave concern is the escalation of Russia’s rhetoric on nuclear weapons since Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine in February 2022.

Just before Easter, Russian analyst Dmitri Trenin, once known as relatively independent-minded but now fiercely loyal to the Kremlin, published an article that raised eyebrows among the west’s Moscow-watchers.

Trenin discussed a statement, issued by the US, France, the UK, China and Russia just before the invasion, which declared that a nuclear war could not be won and must never be fought. Trenin dismissed this statement as “a relic of the past” and said Russia’s nuclear doctrine should be adjusted accordingly.

Meanwhile, Russia in November officially revoked its ratification of the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, drawing the following rebuke from the EU:

This takes place in the context of [Russia’s] illegal war of aggression against Ukraine and after months of irresponsible nuclear rhetoric and threats, some specifically pointing at a resumption of nuclear tests.

All EU governments have ratified the test ban treaty. For the US, president Bill Clinton signed the agreement in 1996, but it has never been ratified by the Senate.

Finally, Putin announced last year that Russia would move tactical nuclear weapons into Belarus — the first such deployment outside Russian territory since the Soviet Union’s collapse. Alexander Lukashenko, the dictator of Belarus, said this transfer had been completed in October, as highlighted in this map by the Council on Foreign Relations.

De Gaulle’s question

Unquestionably, these are nerve-testing times for Europeans. What should they do? A famous question asked in 1961 by General Charles de Gaulle, the late French statesman, continues to resonate.

In the US state department archives is a memorandum of a conversation in Paris between de Gaulle and President John Kennedy. It quotes Kennedy as saying, with regard to a potential nuclear confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union: “The General himself had asked whether we would be ready to trade New York for Paris.”

France acquired its own nuclear deterrent partly because there could never be a definitive answer to the question of whether a US administration would be prepared to risk the annihilation of a major American city, if the Kremlin destroyed a major European city and the US retaliated by striking the USSR.

A French umbrella for Europe?

De Gaulle’s question is relevant because it would arise, in a revised form, if the US removed its nuclear umbrella over Europe and France was called upon to replace it. In other words, if Tallinn were destroyed, would France risk the annihilation of Paris?

In this valuable commentary for the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Liviu Horovitz and Lydia Wachs express doubts about a French nuclear guarantee for Europe:

The main issue is that extended nuclear deterrence — i.e., the threat to use nuclear weapons to defend an ally and thereby run the risk of a nuclear counterattack — is not very credible per se.

Macron’s ambiguity

President Emmanuel Macron’s stance on these matters is not 100 per cent clear. At times he has stated that France’s vital interests — the kind that it defends with its nuclear deterrent — have a European dimension.

On the other hand, he said in October 2022 that a Russian tactical nuclear strike “in Ukraine or the region” would not put vital French interests at risk.

Writing for Estonia’s International Centre for Defence and Security, Philippine de Lagausie sums up:

Macron seems to be advocating not a European deterrent based on French nuclear forces, but rather the construction of a European strategic culture and a dialogue between European partners on the French nuclear deterrent and its role in ensuring the security of the European continent.

A British nuclear commitment to Europe

Europe’s other nuclear power, the UK, is no longer in the EU. But Sir Malcolm Rifkind, a respected former defence and foreign minister, is not alone in suggesting (in this article for The Times) that the risk of a Trump second term raises urgent questions:

We and France will need to develop a new nuclear deterrent strategy, for our own safety and that of Europe as a whole …

Now we must work with Germany and all of our European neighbours to ensure that if Trump becomes president again and carries out his stated threats, Europe’s combined conventional and nuclear weapons will be able to protect democracy and freedom in Europe.

Sir Keir Starmer, leader of the opposition Labour Party, which is favourite to win the next UK election, this week reaffirmed his “unshakeable” commitment to keeping the British nuclear deterrent.

How does Germany fit in?

A somewhat unfocused debate about nuclear weapons has rumbled on in Germany since Trump’s 2017-2021 presidency, as highlighted in this February 2017 article by the FT’s Frederick Studemann.

For the most part, this doesn’t involve serious discussion of whether Germany should acquire its own nuclear deterrent — a step that would violate the commitment to non-nuclear status that the government reaffirmed in the 1991 treaty that paved the way for German reunification.

But some politicians do talk airily of an “EU nuclear deterrent”. Karl-Heinz Kamp pours scorn on such proposals in an article for the German Council on Foreign Relations:

Given that the EU lacks a unified government or a head of state capable of nuclear command, how this would materialise remains uncertain. Clearly, such decisions can’t be made during lengthy night sessions in Brussels that end in a majority vote.

Dieter Dettke, writing for The Globalist, suggests instead:

Germany must use its industrial base as well as its economic and financial resources to enable a European nuclear deterrence capability.

The way forward

It’s conceivable that France, the UK, Germany and other European Nato members such as Italy and Poland will start developing new ideas about common nuclear deterrence.

I ask this question: in the absence of a US security guarantee for Europe, who would have their finger on a European nuclear button?

What does the future hold for Nato? — A books review essay by Yuan Yi Zhu, assistant professor of international relations and international law at Leiden University, for History Today

Tony’s picks of the week

-

After decades when inflation, interest rates and wage growth were all near zero, Japan is on its way to becoming a “normal” economy again, according to central bankers and government officials. The FT’s Kana Inagaki and Leo Lewis report from Tokyo

-

Russia’s banning of X and Meta since its 2022 attack on Ukraine has helped to push Telegram into social media dominance, Olga Logunova writes for Riddle, a website for Russia-watchers

Recommended newsletters for you

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe