IMF: Middle East oil shock would lead to higher interest rates

The International Monetary Fund has predicted that central banks would raise interest rates if the Middle East crisis triggered a sharp surge in the oil price.

My colleague Larry Elliott pressed the Fund on this issue in Washington today, asking:

Q: Is there a risk that the conflict between Israel and Iran will be the next malign shock to the global economy? How do you think it would affect the global economy?

IMF chief economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas replies that the Fund is watching developments, and adjusting its scenarios and analysis.

It is evaluating various possible trajectories for the global economy, including a scenario where there is fairly significant disruption in oil markets that leads to a 15% rise in oil prices, and increased shipping costs.

Under that scenario, the 15% rise in oil prices lifts global inflation by 0.7 percentage points.

Gourinchas says this scenario would impact business confidence, and investment.

And it would lead to higher borrowing costs, he predicts, as central banks tried to dampen down inflationary pressures.

Gourinchas says:

The increased inflation that would come from higher energy prices would trigger a response from central banks that would tighten interest rates in order to secure inflation coming back to target, and that would weigh down on activity.

It would do so in a context in which, in some countries, activity and growth is already fairly weak, so that might also have a strong effect there.

Key events

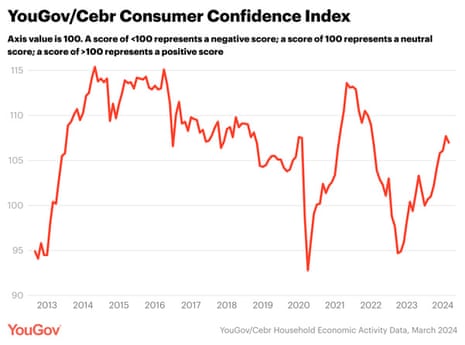

UK consumer confidence has fallen for the first time in seven months, YouGov reports, as people grow less optimistic about the economic outlook.

Its confidence index has fallen for the first time since July 2023, due to decreases in household finance, business activity, and job security metrics.

European banks are having a bad day.

The Stoxx 600 Banks index is down 2.5%, on track for its worst day since August.

Lloyds is down 3%, HSBC has lost 2.9% and Barclays is 2.6% lower.

FTSE 100 on track for worst day in nine months

Britain’s stock market is on track for its worst day since last July, as investors grow more fearful.

The FTSE 100 index is now down 155 points this afternoon, or 1.95%, at 7809 points, which is a three-week low.

This would be the biggest one-day fall in nine months, as investors continue to worry that central bankers will be slower to cut interest rates than hoped.

Grocery technology firm Ocado are the top riser, down 5.2%, followed by tech investor Scottish Mortgage (-4.3%). Mining giants are also among the top fallers

Nearly every one of the hundred stocks in the index are in the red, with only chemicals maker Croda (+2.5%) and energy firm Centrica (+0.7%) keeping above water.

Market sentiment has been hit by “simmering Middle East tensions, a tepid opening to the earnings season and further economic data showing little evidence that the need for interest rate cuts is approaching”, says Richard Hunter, head of markets at interactive investor.

Hunter adds:

Investors are keeping a close eye on the developing situation in the Middle East and assessing the likelihood of retaliatory action from Israel following the weekend’s Iran attack.

One such side effect has been an oil price which remains up by 17% this year, despite flattening out after its recent hike, but which nonetheless remains an inflationary factor which complicates the desired direction of travel for global central banks.

European stock markets are also a sea of red, with Germany’s DAX and France’s CAC both down 1.6%.

This follows losses in Asia-Pacific markets, after falls on Wall Street yesterday:

⚠️BREAKING:

*ASIAN STOCKS SINK ACROSS THE REGION ON MIDDLE EAST WORRIES, FED RATE JITTERS

🇯🇵🇨🇳🇭🇰🇰🇷🇮🇩🇮🇳 pic.twitter.com/JgMAuPh37x

— Investing.com (@Investingcom) April 16, 2024

The IMF is urging the UK to rebuild its fiscal buffers ready for the next crisis, rather than undermine them with tax cuts.

The Fund was asked today for its view on Jeremy Hunt’s budget:

Q: Is the IMF comfortable with the British approach of cutting taxes on an assumption of further unspecified cuts to public spending?

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas says that a number of countries who deployed fiscal buffers during the pandemic and the cost of living crisis have seen their debt/GDP levels rise.

We are calling for the rebuilding of these buffers, so countries can deal with future shocks, he says.

The UK needs to rebuild its fiscal capacity, he says, as do many other countries including the US.

This is important, Gourinchas adds, as countries which had the fiscal room to protect households and businesses during these two crises did much better than those who did not.

IMF: Middle East oil shock would lead to higher interest rates

The International Monetary Fund has predicted that central banks would raise interest rates if the Middle East crisis triggered a sharp surge in the oil price.

My colleague Larry Elliott pressed the Fund on this issue in Washington today, asking:

Q: Is there a risk that the conflict between Israel and Iran will be the next malign shock to the global economy? How do you think it would affect the global economy?

IMF chief economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas replies that the Fund is watching developments, and adjusting its scenarios and analysis.

It is evaluating various possible trajectories for the global economy, including a scenario where there is fairly significant disruption in oil markets that leads to a 15% rise in oil prices, and increased shipping costs.

Under that scenario, the 15% rise in oil prices lifts global inflation by 0.7 percentage points.

Gourinchas says this scenario would impact business confidence, and investment.

And it would lead to higher borrowing costs, he predicts, as central banks tried to dampen down inflationary pressures.

Gourinchas says:

The increased inflation that would come from higher energy prices would trigger a response from central banks that would tighten interest rates in order to secure inflation coming back to target, and that would weigh down on activity.

It would do so in a context in which, in some countries, activity and growth is already fairly weak, so that might also have a strong effect there.

The IMF still expects the Federal Reserve to start cutting interest rates this year, even though US inflation has been higher than forecast.

IMF chief economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas tells reporters that:

We would still expect the US to be in a position where it starts easing sometime in 2024.

Progress has been “enormous” in terms of disinflation, and in the resilience of economy, he adds.

IMF: 15% rise in oil price would raise global inflation 0.7pp

Q: What’s the energy price outlook, as the US considers new sanctions on Iran?

The IMF has drawn up a scenario exploring the impact of rising geopolitical tensions, with elevated energy costs and higher shipping costs.

This would lead to higher price pressures in the global economy, higher inflation, and lower output, says Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas.

Gourinchas tells reporters in London that the IMF believes a 15% increase in oil prices would increase inflation globally by 0.7 percentage points.

We are not in that scenario now, though, he insists, adding it is too early to say if the current increase in oil prices will be sustained.

IMF: low-income developing countries suffering more scarring

The IMF are now taking questions in Washington on its new World Economic Outlook.

Q: What scarring is occuring in low-income developing countries, as they try to recover from the pandemic?

IMF chief economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas says the Fund has lowered its estimate of economic scarring for most regions and countries, but increased for low-income developing countries.

Those countries are suffering an impact both on output, and on high price pressures, he says. That’s due to high energy and food prices, an increase in food insecurity, in a region that had smaller buffers to protect their population.

Rising interest rates mean these countries have less fiscal space too.

The World Bank warned this week that the pandemic has brought poverty reduction to a halt:

The US fiscal stance is “out of line with long-term fiscal stability”, IMF chief economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas adds.

That’s a sharp nudge to Washington policymakers that the US deficit, which rose to $1.6 trillion in the 2024 fiscal year, is too high.

Fiscal consolidition is never easy, but is better done before markets dictate it, Gourinchas points out.

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the IMF’s chief economist, is telling reporters in Washington that the global economy continues to display remarkable resilience, with growth holding steady and inflation declining.

But many challenges lie ahead, Gourinchas adds.

Risks are now broadly balanced, he explains.

Downside risks include new prices spikes from geopolitical tensions, persistent core inflation, or a disruptive turn towards fiscal adjustment could slow activity

On the upside, faster disinflation, or more timely structural reforms that boost productivity could support activity, Gourinchas.

Gourinchas also warns that we are “not there yet on inflation”, as progress towards bringing inflation down to target has stalled since the start of the year in some countries [such as the US].

The IMF are hopeful that the world economy will achieve a ‘soft landing’ (lowering inflation without causing a recession).

Full story: UK households face second year without improved living standards, says IMF

Larry Elliott

Britain’s households will endure a second year without an improvement in their living standards in 2024 as the effects of high inflation take time to abate, the International Monetary Fund has revealed.

In its flagship World Economic Outlook (WEO), the Washington-based IMF said it was forecasting modest 0.5% UK growth this year – but only as a result of a rising population.

Growth per head – one of the key measures of living standards – is expected to remain flat this year after a 0.3% drop in 2023.

The IMF said there would be a pick-up in the economy as 2024 wore on – something the government is banking on to reduce its opinion poll deficit with Labour – but it would not be until 2025 that the cost of living crisis would be over.

Although official figures due out on Wednesday are expected to show a fall in the UK’s annual inflation rate to about 3%, the IMF believes the Bank of England will be cautious about cutting interest rates, and has pencilled in only two 0.25 percentage point cuts in official borrowing costs this year.